Bringing lessons from Japanese temple constructions to software maintenance

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Don’t entomb your applications. Make them flexible, be ready to make gradual changes. That way, they won’t need an overhaul from scratch when the time comes.

Introduction

The new software engineer wanted to start our project from scratch. He had joined our squad two weeks previously. It’s all so old and messed up, he said. It’d be quicker to do it from scratch. It sounded tempting, but the memories of past rewrites and projects lingered. They promised reset but delivered chaos. There was a better alternative.

The idea of a complete rewrite is an alluring siren song. Tempting but ultimately counter-productive. Legacy code is vilified, considered inefficient and outdated. It’s seen as a burden begging to be replaced. But is tossing everything aside ever the answer? Almost never.

The Siren Song of the Rewrite

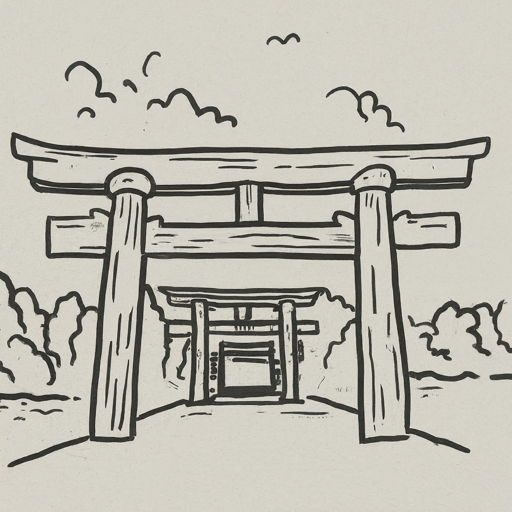

Let me propose a different approach: the eventual, or gradual, rewrite. Imagine your application to be the Ise Jingu shrine in Japan. It is carefully, cyclically rebuilt every twenty years. We too can gradually modernize our software, piece by piece. We don’t have to give in to the disruptive temptation of starting from scratch. We will explore the “gradual rewrite” philosophy in this essay. I argue that it offers a sustainable and cost-effective solution for managing software lifecycle.

Maintaining existing systems, specially old and creaky ones, is lame. Without understanding the business or engineering decisions behind technical choices, it’s hard to appreciate an application’s choices. It’s easy to dismiss choices made by others at an unknown past as inefficient and incorrect. They made during the dark ages, one can argue. An era when efficiency, ease of development or testing were unaccounted for. Armed with an ‘enlightened’ perspective of hindsight, teams convince themselves that their solution is future-proof and perfect. Once such conversations begin, interest in maintaining and improving old code goes away. The legacy system is treatedmuch like a leper colony. A clean start is the only viable option considered, uninfected by the diseases of the yore.

But a clean rewrite takes precious development time and resources away. Revenue-generating features that could increase a products viability are pushed back. Fixing potential regressions in the end is as overwhelming as the rewrite itself. Does one match the initial app bug-for-bug? What if the downstream teams have the bug as a part of their workflow, as is standard in many b2b applications? The questions and problems keep on coming. Until one day, when the new rewrite is the legacy app.

Learning from the Ise Jingu Shrine

Let’s look for a parallel in a different field: construction. Every 20 years, locals tear down the Ise Jingu grand shrine in Mie Prefecture in Japan, and rebuild it anew. This has been happening since around 8th century CE. The temple has been reconstructed about 65 times. The builders have maintained the cultural continuity in architecture. The reconstruction is a fundamental part of the temple’s upkeep. The locals have achieved goals in conflict with each other. The original architecture and intention behind the construction is preserved. However new construction uses modern construction materials and techniques. The reconstruction is budgeted as periodic upgrade, it’s build into the Temple’s finances.

Is there anything we can learn from this tradition in in software? Can it help us deal with the legacy-code allergy?

I call my proposed solution ‘eventual/gradual rewrite’. If there’s a part of application that’s specially inefficient, it might be replaced with newer versions of library code. That would be the temple replacing worn-out wood beams with new ones. If new features are needed, a second buildchain could be added. Some core functionality could be offloaded to binary generated by a different programming language.

The Eventual Rewrite Philosophy

The eventual rewrite proposes a piece-by-piece modernization approach. Here’s how it works:

- Targeted Updates: Replace inefficient parts with newer library code.

- Modularization: Introduce separate buildchains for new features, reducing codebase complexity.

- Cyclical Improvement: Schedule regular upgrades and partial rewrites to minimize churn and duplication.

An “eventual rewrite” upgrades parts of software while preserving its core functionality and form. Compare that to how the temple rebuilds use new materials and technique while retaining original design. Technical debt and outdated dependencies can be selectively re-written – perhaps in different languages – without bringing everything down. In high-interest environments, budget runways are limited. As you run out of gas, would you want a car that might one day be built to run faster, at great current cost, or one that currently works whose parts you will eventually change to form a new car?

There are downsides, of course. One is that while it would save on runway and speed-to-market, it would make the system more complicated. But the goal is to future-proof the system. Maintenance challenges move towards the right direction because more of the codebase is updated, and easy for new engineers to work on. Just like traditional woodworking artisans work together with modern construction techniques, CnC machining and 3d printing, the legacy code can exist with updated code. Change is a fact of life, and if a piece of software needs to be future-proof, it must be forward-looking.

To put it differently, software should never be considered ‘complete’ as long as it is ‘living’. If one needs to apply updates, fix bugs, add more features, it’s an ongoing project.

Exceptions to the Rule

There are exceptions to this. Simulation and linear optimization programs written in COBOL in the 1980’s are feature-complete and still chugging along. They haven’t needed bolted-ons by python-java-c-c++ appendages. Craigslist has stood the test of time for the past quarter century withlittle changing. Power plants and military installations likely don’t have changing needs, apart from the rare security update that might be needed. They might be okay mummifying their applications, yours probably needs to be living and organic.

A difference of workflows

This simple diagram will hopefully explain the merits of a gradual system overhaul. Unless the new system is drastically different from what exists, maintaining two sets of features and bug fixes is resource intensive and delays the eventual system upgrade.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

+-------------------+

| Legacy Codebase |

+-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

| Feature 1 | | Feature 2 |

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

| Bug Fix | | Integration |

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

Eventual Rewrite:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

+-------------------+

| Legacy Codebase |

+-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+

| Updated Library 1 |

+-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

| Feature 1(updated)| | Feature 2 |

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

| Bug Fix | | Integration |

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

Complete Rewrite:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

+-------------------+

| New Codebase |

+-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

|Feature 1 (rewrite)| | Feature 2(rewrite)|

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

|

v

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

| New Bug Fix | | New Integration |

+-------------------+ +-------------------+

Building Software Like Building Structures

There’s a reason people don’t like to budget in continuous development for a software’s lifetime. They are used to thinking of software in terms of physical infrastructure. They visualize long-lasting constructions like the Roman amphitheaters that have stood for thousands of years. That is a misleading comparison. It assumes that good software should be built once to perfection and never touched again. If there’s additional requirements, it’s time for a complete rewrite. But the Italians don’t watch movies or organize their school plays inside the millennia-old arenas. They have needed new modern theaters. So too must new from-scratch development happen for similar-but-different uses. But that comparison still misses something important. Imagine if the original engineers and architects of the Colosseum had anticipated modifications. They’d somehow forseen the need for parking lots, comfortable seats, table service, 3d surround sound systems, and so on. They would then have under-built the original piece, and instead earmarked budget for adapting to future needs.

Building large, complicated pieces of software is like building a large building. They both involve a relatively long and complicated process that needs good planning. They require teams of experts with different levels of expertise to collaborate. They have the goal of achieving a specific initial vision. With churn in the composition of team, the original vision becomes less clearly defined. Somebody decides their new and improved(!) vision should replace the existing one. But buildings don’t change significantly the longer they’re built, nobody decides to start from scratch because actually the foundation-constructing technologies changed in the last two years. We should treat software the same way.

Beyond Agile vs. Waterfall

This comparison is not just the difference between Agile and waterfall methodologies of Software engineering either. A team can be perfectly Agile in creating a product, consider it ‘complete’, and fall into the rewrite trap as soon as a certain ‘threshold’ of team knowledge and original vision is lost.

The idea is to reject rewriting software replacement from scratch every X years. Change it gradually like the ship of Theseus. Software development stacks and philosophies can change, generally accepted wisdom in the industry can turn around. Change can come from anywhere, from changing demographics to change in taste, of customers and of customers. We must write our systems to integrate those changes without starting from scratch. Good planning involves strategizing ways to deal with such changes in advance.

Conclusion

Don’t entomb your applications, make them flexible, ready to make iterative changes. That way, they won’t need an overhaul from scratch when the time comes.

A related discussion can be found here. That is what originally inspired me to write this piece.

Image credit: Ukiyo-e depicting the Sengū ceremony (relocation of kami) when it was rebuilt in 1849. by Hiroshige, 1849, via Wikipedia